Hull Inspections – Condition-Based Maintenance

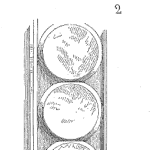

By the 1906 revision of the Regulations, there were many more technical changes to manage. Most ships now had iron or steel hulls, which changed the mechanism of how a hull would fail. Galvanic corrosion and methods to prevent it were well understood. The chapter covering “Preservation, Repairs, and Docking” required zincs, the sacrificial anodes to be placed near the screws to prevent galvanic corrosion.

[Read more…]